Stop using pip freeze to create a requirements file

Dependency management be complicated sometimes

Intro

Dependency management can be a fickle thing across languages; In Android development, you list your dependencies in the build.gradle file, while in Node.JS, you list dependencies in the package.json file. Python’s equivalent to this is requirements.txt, and it is exactly what it sounds like: a text file full of python packages (or requirements) to make your application run properly.

Across the board, dependency management seems like a fairly manual process. Sometimes when you’re deep into working on an application, you don’t really think of the dependencies you’ll need before-hand, and end up installing some on the fly. This becomes a problem when you want to write your requirements.txt file (which you should write in to make your application portable) and can’t actually remember the package name that you ended up using. Or on the converse, you ended up installing a number of packages, but don’t actually use a majority of them. You don’t want those extra packages installed and lying around because if you were to build a docker image of your application, those extra dependencies would increase the build time of that image. Not to mention that packages that share the same dependencies but have different version requirements, got handled in special ways under-the-hood by pip.

A standard practice I’ve seen to remedy this problem is to run pip freeze > requirements in order to print out all the packages you currently have installed and output them to a file. Doing this definitely has its benefits because it then pins all the dependencies you currently have installed, and you don’t have to worry about remembering each package you installed while developing. But there are also some drawbacks to doing this that you might not immediately see. I am going to to highlight two (2) issues I see with creating your requirements file like this, and ways you can potentially improve managing your dependencies.

Freezing creates ambiguity around top-level dependencies

As I said above, running pip freeze gives you a list of all currently installed dependencies, but that does mean all of them. Chances are that you’re not paying attention to the dependencies that your dependencies require (second-level dependencies).

Let’s use this fairly short list of dependencies as an example.

Seven (7) dependencies honestly doesn’t seem like much, so then why am I making such a big stink about this? Well, let’s think a little bit deeper on this.

These 7 dependencies each have their own dependencies, which may in turn have their own dependencies (and so on, and so on). If we take the packages in the above list, install them, and then pip freeze them, we see a slightly different story.

As you can see, the number of dependencies on this list has doubled, because pip freeze accounts for your second-level, and tertiary-level dependencies. I want to be clear that this is not inherently a bad thing either, making us aware of our second-level dependencies is typically a good thing.

The question I want to pose is: “Which of these are the top-level dependencies? Which of these packages do you directly work with in the code?”

If you’re the one that created this requirements file, then you’ll likely know which of these are your main dependencies, but if you’re someone that has inherited this code from elsewhere, then you would have no idea! Sure you can make some educated guesses or try to trace it by looking at the documentation, but in this format, its not quite clear which is a top-level dependency vs which is a second-level dependency. And quite honestly, the above example was using the assumption you’ve created a virtual environment beforehand, and are executing these commands within it. If you’ve not created a virtual environment, you’ll get a lot more unrelated or ambiguous dependencies listed if have any top-level packages installed for your python version.

Freezing doesn’t account for dependency versioning conflicts

A probably lesser-known piece of information is that not every top-level dependency pins its second-level dependencies. What exactly does this mean?

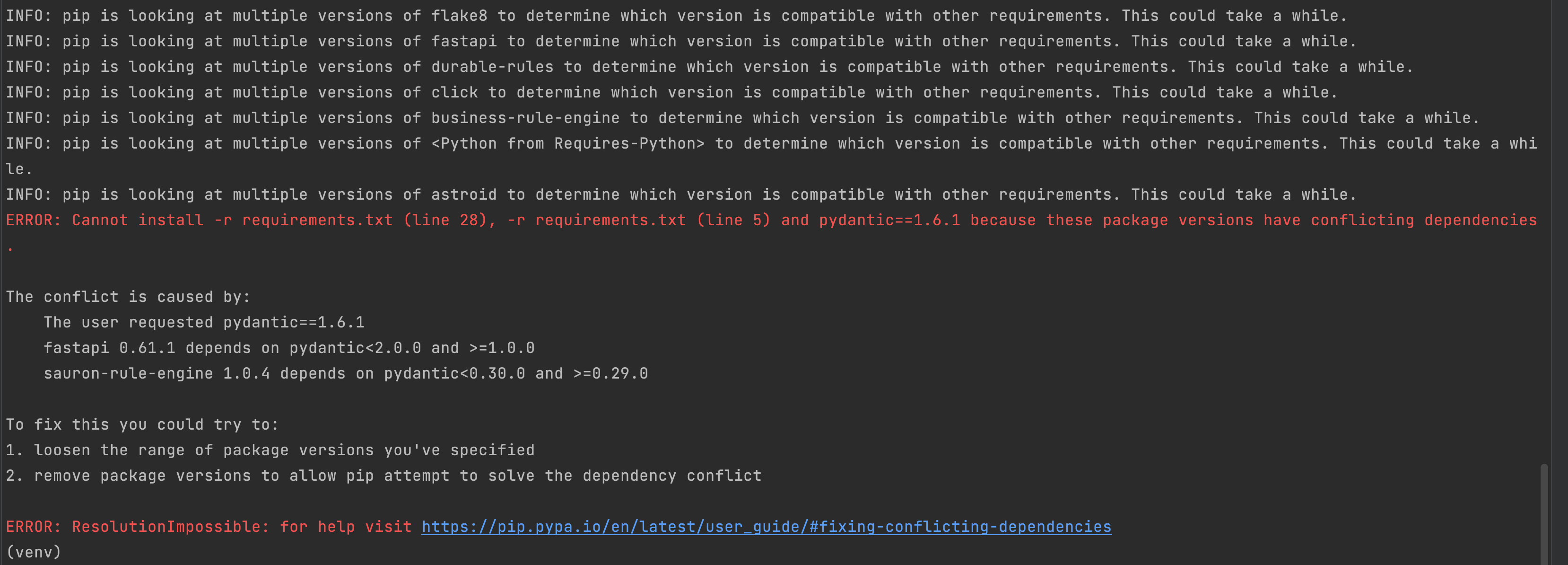

In short if you run pip install -r requirements.txt on the following listed dependencies, it will fail citing a dependency conflict

How did we even get to this state? I actually don’t know; this dependencies list came from code that my team inherited, so I truly have no idea which packages from this list are top-level dependencies or not. What I can surmise from this is that whoever created the file likely did a pip freeze in order to do so.

Luckily I was able to work backwards from this and deduce that the following are the top-level dependencies in use:

You might notice that one of the dependencies giving us trouble (sauron-rule-engine) wasn’t actually even used in the code! Coning to this discovery led me to an even more important realization:

When we treat both top-level and second-level dependencies as top level, we hamper pip’s ability to intelligently manage second-level dependency version compatibility

And pip tells us just as much in the above error message.

Had I wanted to keep the sauron-rule-engine package, the fix here would be to not specify the versions for all 3 packages (sauron-rule-engine, pydantic , and fastapi), that way pip would be able to intelligently resolve conflicts under-the-hood and get the packages installed. The problem this now imposes is that if I’m wanting to use new functionality from the latest version of one of these packages, I may be unable to do so because pip decided to install an older version of the package.

Whats the best way to manage your dependencies?

It is definitely a cliche answer, but really how you decide to manage your dependencies is up to you. What i’ve noted above are just potential issues you may run into using pip freeze, but that in no way means to never use it. For simple projects where not many people will be needing to understand the code, then I’m sure it’s fine to do. I avoid using it myself for the reasons listed above.

Some alternatives to using pip freeze are:

- Hand-curate your requirements.txt file. Sure it’s not the easiest solution in the world, but you’re at least verifying that your requirements file isn’t just broken if you happen to hand it off to another team or individual. You’re also making it very clear what your top-level dependencies are if anyone besides yourself or your immediate team members are looking at your project.

- Use a simple dependency manager like pip-tools (https://github.com/jazzband/pip-tools) to generate your requirements.txt file for you. Pip-tools allow you to create a file with just top-level dependencies. Then when pip-compile is run, pip-tools creates your requirements.txt for you with all of version compatible second-level dependencies. And example of this is below

Conclusion

Hopefully this post has given you an idea of the problems that running pip freeze can introduce. This is also not to say to never use it, but really just use your best discretion on if doing a pip freeze will help you and your team in the long run. In the meantime, check out pip-tools to help make the dependency management process a lot easier!